“We submit ourselves to profound constraints borne out of the desire to uphold the stereotypical.”

These were the words of my mentor and grandfather, Dee Uguru. He was a man who’d been thoroughly schooled by experience. Up until his death, he still could not fathom why anyone would wait to be spoon-fed by a teacher. “Put me in a room with those your knowledge hawkers, and they’ll be in for a ride”, he’d say. Although he said this as a joke, I knew he meant every word, even at my young age. He was one of the few people whose free-spiritedness ran deep and reflected through his eyes.

To him, the truest form of happiness is the one that springs from within. Waiting on others is like wandering the earth in search of where the firmament ends. He chose neutrality in a society where respect is synonymous with affixing titles to those ahead of you in age. He believed titles were an unnecessary absurdity and lived his life like no man’s business.

I was jerked back to reality as the siren which heralded Nepa light blared nonchalantly from the opposite compound. I could hear the jubilation of my neighbour’s children from the next room. By the corner, the table clock ticked away lazily. It was ten-fifteen in the morning, and hunger lashed at my intestines like a sickle on a flower.

I shook off the thought of my grandfather from my head and staggered to my feet. I went to the corner where my pots and plates lay unwashed with tiny insects hovering over them and searched frantically for leftover food but was greeted with the sour odour from the oha soup I concocted two days ago. I hissed and cursed in disappointment. I picked up my bucket and towel and made for the door.

There is a saying that who you see first in the morning plays a significant role in how your day will play out, so I prayed not to see Kakapo, my neighbour, a middle-aged woman who was nicknamed after a parrot as a result of the strong characteristics which she shares with the bird. She was plainly a chatterbox. Nothing went unnoticed under her nose.

As I came outside, there was Kakapo nursing her baby in the corridor. “Ah! Yellow pawpaw. You don wake? This one wey you no comot early today wetin happen?”. I hissed and strode for the bathroom. “No be fight na”, she called after me. I filled my bucket with cold water and carried it down the corridor where the general bathroom awaits in all its filthiness.

This was one place I dreaded to be. I summoned courage, pushed open the door caked in dirt with my legs, and peered inside. Each scoop of water poured on my skin stung like the bite of a soldier ant. Today was yet another day to hit the streets of Lagos. Not in search of a job as I had continually done for the past one and half years, but to actually begin working one.

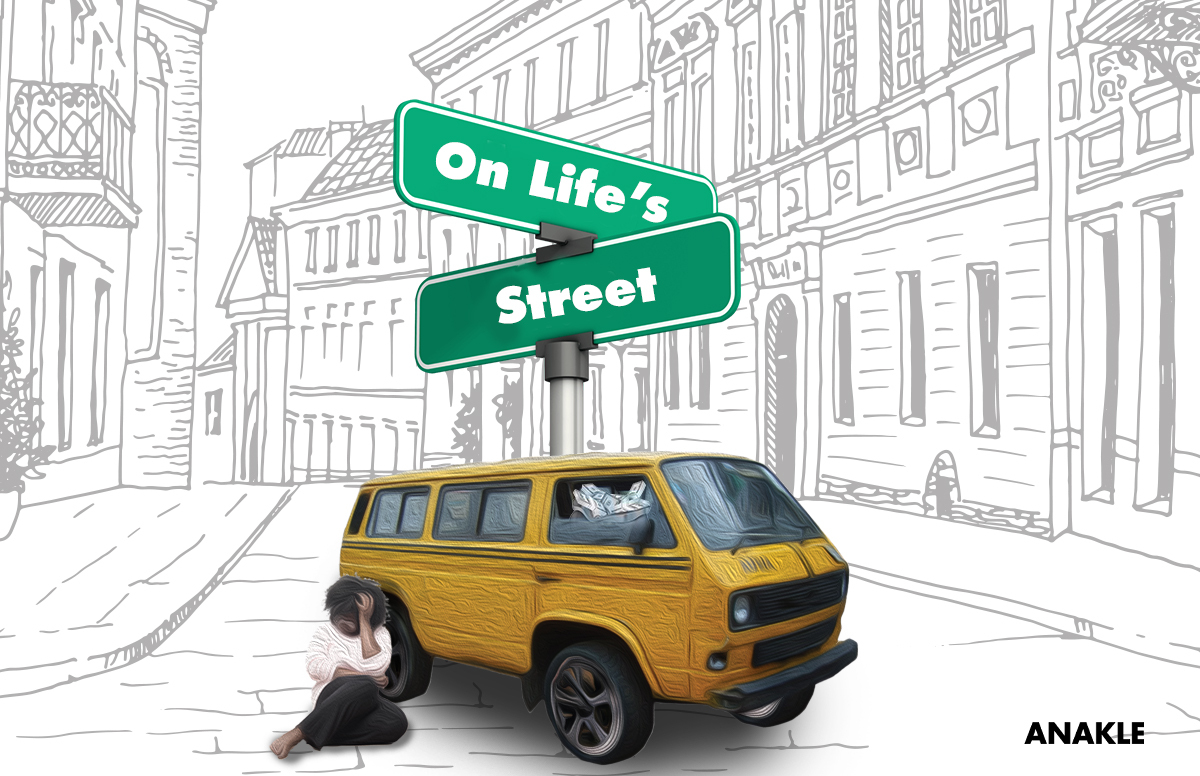

I had met with Chief Bamidele some weeks back, and after much convincing, he had agreed to give me the only job he could. I was going to be a danfo driver. The mere thought of it sounded ludicrous. Imagine bumping into an old acquaintance, and when they asked what I was doing now, I’d say, “I’m a danfo driver”, or no, maybe I’d simply say I’m in the transport business.

I hurriedly left the house and arrived at the park. As I sat at the wheel, my heartbeat was so loud that I feared the man sitting across from me would hear it. I stepped on the gas pedal and hit the streets. Of course, as I had envisaged, the pitiful stares were forth-coming in full force, and I could feel the hair on my skin stand. Female danfo drivers were a rare sight and I could understand that. More times than I can remember, I had to remind myself I was in a one-man race or one-woman race if I dare say. Only a fool would be ashamed of what puts food on their table, and I’m no fool.

Once again, I sought strength in my grandfather’s words “Onye ọ bụla na-agbagharị n’okporo ụzọ nke a na-akpọ ndụ” (Everyone is a hustler on this street called life). My name is Chinasa Okoro and my story has just begun.

By Nneka Ijioma